Supervisors: Dr. Jorg Conradt, Dr. Christoph Richter: TU Munich

This was my project for the summer of 2016, wherein I worked on mathematical modelling of muscles for myomorphic systems, actuated on neuromorphic hardware, as a German Academic Exchange (DAAD) scholar from India. Jargon aside, the project aimed to make a mathematical model of a muscle-like actuator, which would be actuated by a brain-like spiking system.

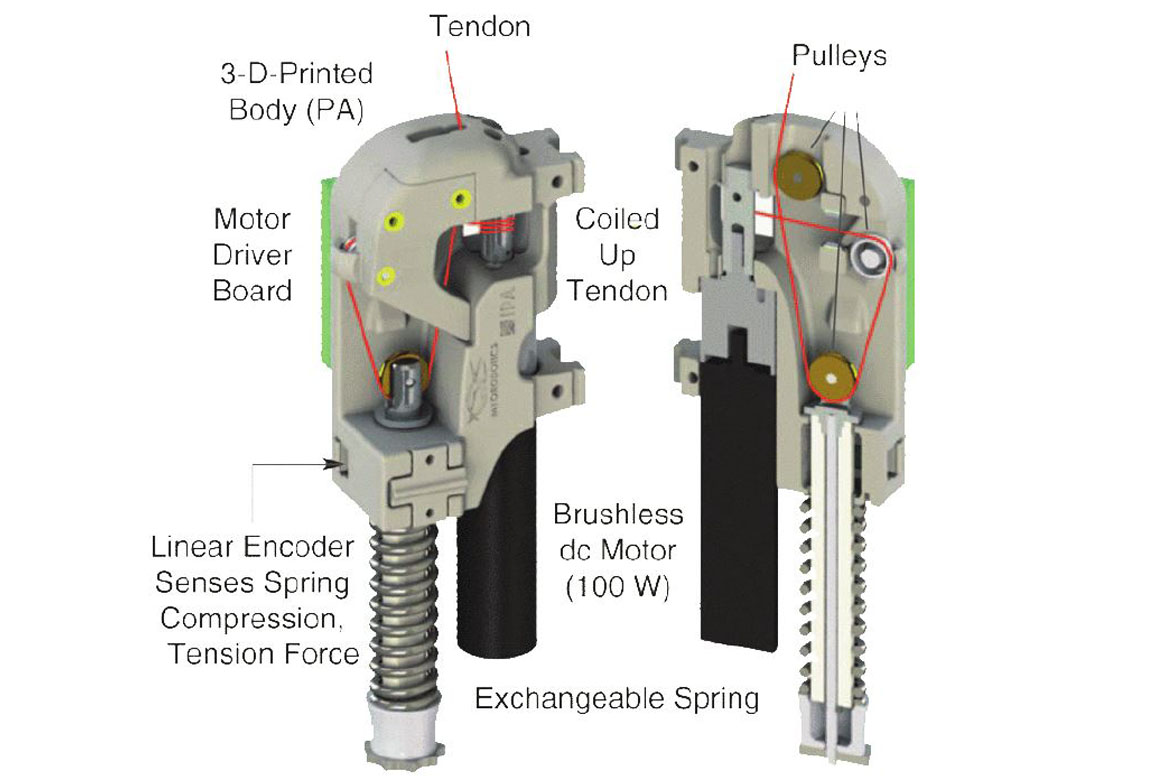

I was a part of the wonderful group Neuroscientific System Theory, a group within the Dept. of Electrical engineering at TU Munich, Germany. We had this idea of using a Myomorphic, or muscle-like hardware system, and actuate it like how the brain actuates biological muscles. A myomorphic robotic arm looks like this:

|

|---|

| Fig 1: Myorobotic arm |

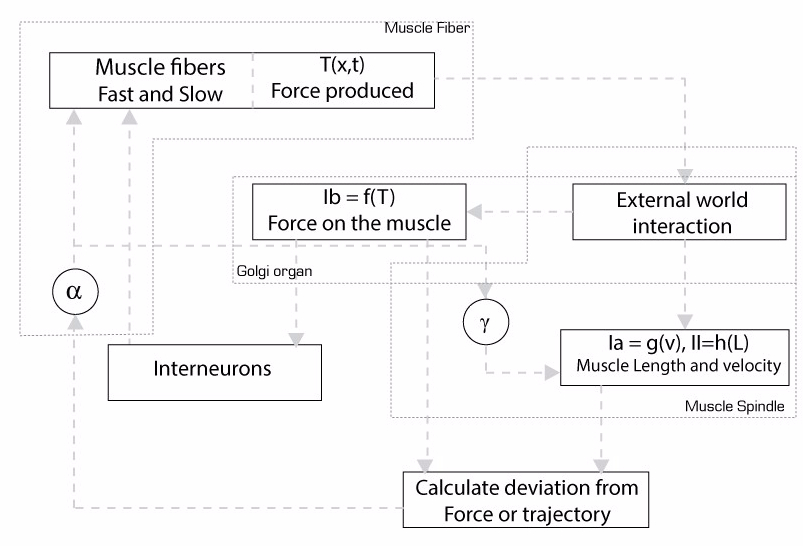

The project was in its nascent stages, and my job as a limited-time intern student was to give it a solid theoretical foundation. I browsed through volumes of measurements and inferred models with the perspective of having a workable implementation. Finally, I was able to make an implementation of models for (i). Golgi tendon organ, (ii). Tendons and Ligaments, and (iii). Muscle fibres. The implementation can be found on github. For artificial spikes, the model worked like a real muscle, while interfacing with a neuromorphic hardware like SpiNNaker was out of scope for the short duration.

Short explanation:

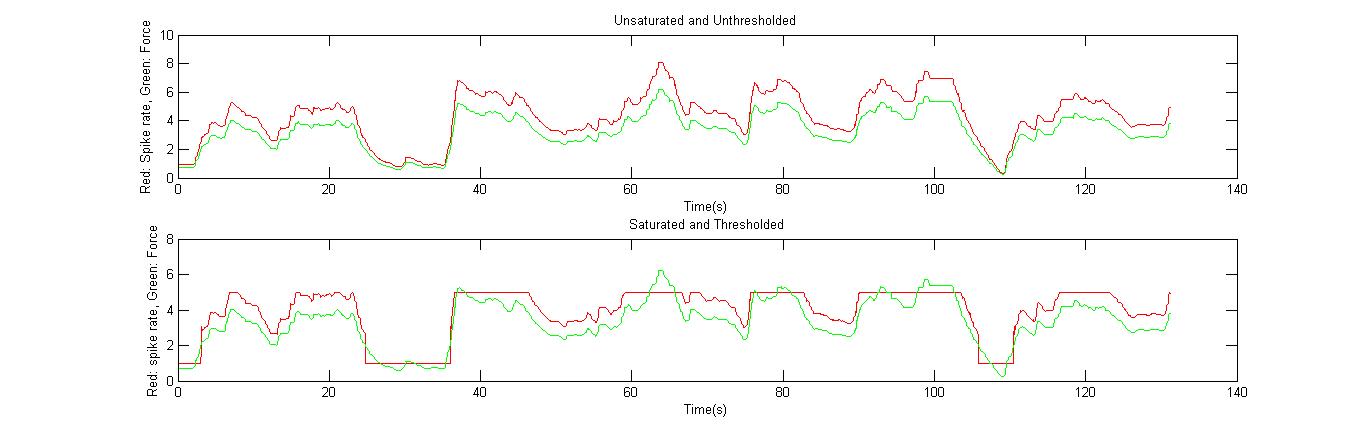

The Golgi tendon organ is the ‘force sensor’ of the body. It is attached between the muscles and the tendons, and gives out ‘spikes’ corresponding to stretch in its length. As all physical systems, it has a ‘threshold’ value, below which it cannot sense any force, and a saturation value, above which it cannot expand any more and sense any incremental change in force. The system is almost linear, and it would perform something like this:

|

|---|

| Fig 2: Golgi tendon Organ response. |

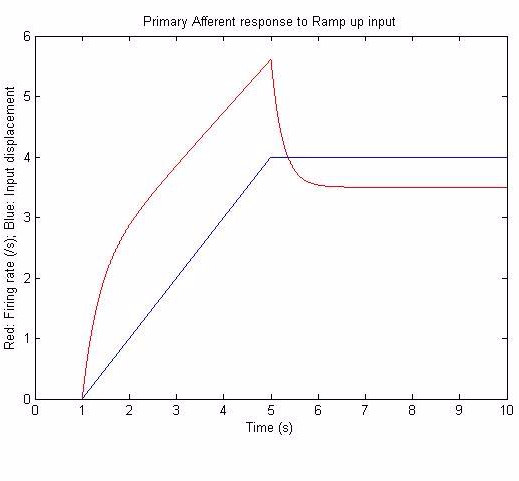

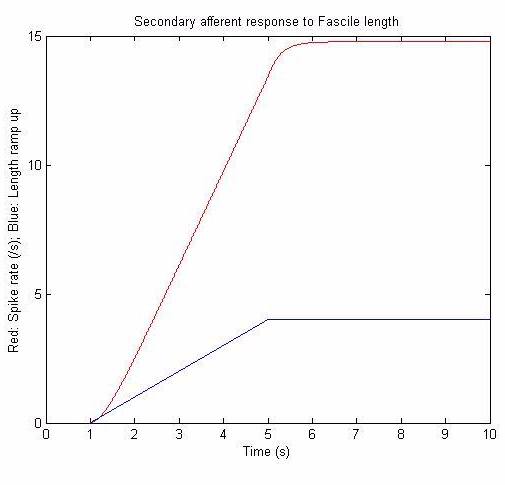

The muscle spindle acts as the ‘actuator’ of the muscle system. However, the force is not the only measurement the Spinal chord needs to make a decision on the spike rate needed for the spindle. The spindle itself gives two kinds of response: Ia and II, or Primary and Secondary afferent actions. How are they different? Well, it relates to an inbuilt feedback in the spindle itself- Ia afferent neurons provide spike rate given length and velocity of spindle, while the II afferent provide spike rate given length. The Type-II relate to the rest length of the muscle spindle, while Type-Ia relates to increments and changes in the muscle spindle. Together with the Golgi Organ which provides Force information ( the net system is non-linear!), the spinal chord makes an informed decision on spike rate for the spindle.

|

|

|---|---|

| Fig 3: Ia response to ramp-step | Fig 4: II response to ramp-step |

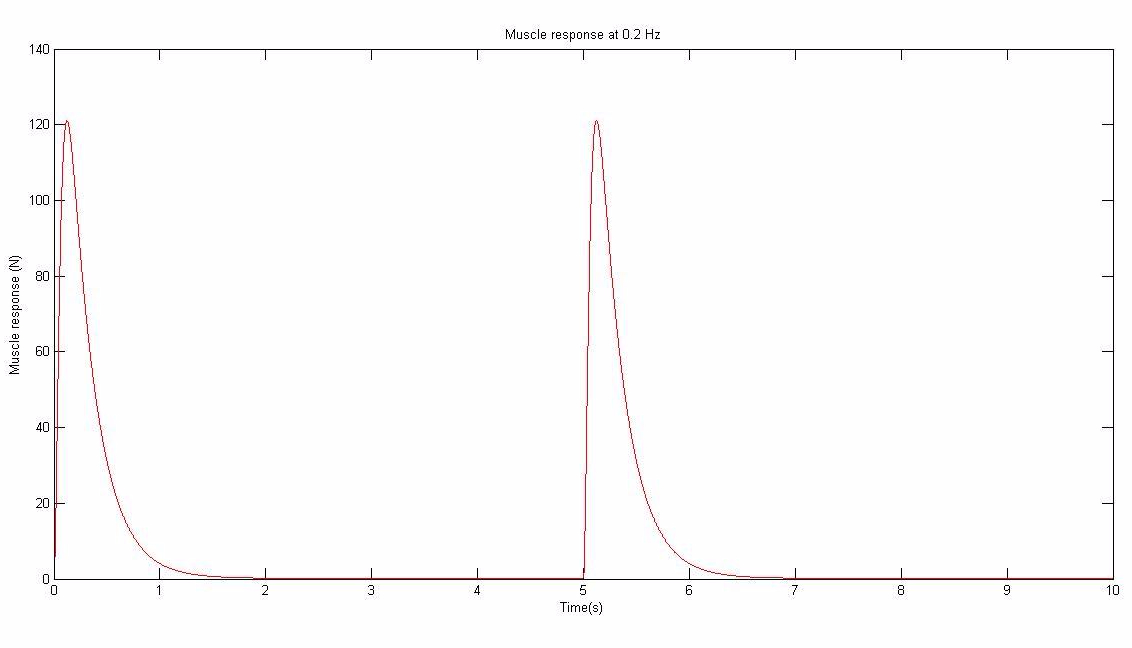

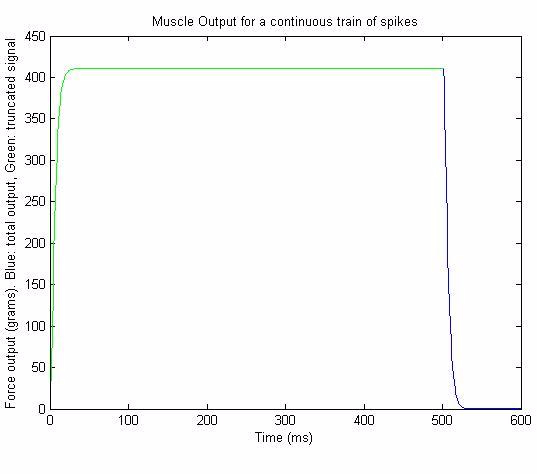

The muscle spindle’s force output is controlled only by the input spike rate from efferent neurons. A single spike generates a ‘Muscle twitch’, and a combination of such twitches gives rise to a general muscle response. The response (obviously) has a saturation, and the simulation of model looks like this:

|

|

|---|---|

| Fig 5: Low frequency spike rate response. | Fig 6: Muscle tetanus, or high frequency rate. Max muscle force. |

So we have a model for the actuator, a model for the sensor, and SpiNnaker, a model for the controller. For a given physical system, we can incorporate these models as interfacing units, and after setting up appropriate conditions for actuation, the system would potentially act as a Myo-morphic system!

Sadly, while we were coordinating with other students to interface the model with Real muscles, and set up a proper implementation, another group beat us in publishing a similar model interfaced with artificial spiking system, which can be found here….

Anyway, that was my part of work in the project, which I hope will be integrated well in the near future!

The project report which we were intending to be the start for our publication can be found here: TUM_FinalReport.

|

|---|

| Fig 7: Muscle model: A flow chart |